Celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Still Faces Pushback

Today is Martin Luther King’s Birthday, the federal holiday that honors the assassinated civil rights leader.

Well, not everywhere.

All 50 states celebrate the public holiday on the third Monday in January, but not all states, cities and towns dedicate it solely to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Some package it as a broader celebration of civil rights, and others combine the holiday with commemorations of Confederate history.

State-by-state naming differences are remnants of fierce opposition to a holiday that was not officially recognized by all states until 1999. Here is a brief history of how Martin Luther King Jr. Day came to be.

How Did Martin Luther King Jr. Day Become a Holiday?

A federal holiday honoring Dr. King was first proposed four days after he was assassinated, in 1968, but it took almost two decades of campaigning for it to be approved and designated at the national level.

In the meantime, according to the King Center, a few Northern states approved the holiday from 1973 to 1975: Illinois, Massachusetts, Connecticut and, by court order, New Jersey.

But state-level momentum slowed and Congress did not act. Advocates led by Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, spent years lobbying for the holiday, testifying before Congress and gathering millions of signatures on petitions.

President Jimmy Carter expressed support for the federal holiday in 1979. The singer Stevie Wonder became a prominent supporter, too, financing a Washington lobbying office and releasing a hit 1980 song in support, “Happy Birthday.”

The campaign finally succeeded in 1983, when Congress passed the King Holiday Bill and President Ronald Reagan signed it into law. The third Monday in January would be celebrated as Martin Luther King Jr. Day starting in 1986.

Who Opposed It?

Proposals to honor Dr. King met strong resistance in Congress, and when the holiday was enacted, many states were slow to acknowledge it. New Hampshire became the last state to officially recognize the holiday in 1999 after years of acrimonious debate.

When the proposal to create the holiday was debated in Congress in 1979, Republicans led the charge against it. The strongest opposition came from lawmakers in the Deep South, such as Senator Jesse Helms, Republican of North Carolina, and Senator Strom Thurmond, Republican of South Carolina, who ran for president in 1948 on a segregationist platform.

Opponents argued that it giving federal employees a new paid vacation day would be too expensive and that it was inappropriate to bestow such an honor upon Dr. King because he had never held elected office, according to an essay by Donald R. Wolfensberger, a congressional scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

When the measure failed in 1979, Representative Cardiss Collins, Democrat of Illinois and leader of the Congressional Black Caucus at the time, said she believed that racism had played a role.

But by 1983, many Republicans in Congress had changed their minds. The King Holiday Bill passed the House and the Senate with bipartisan support and was signed by a Republican president.

But not everyone came around to the idea. Mr. Helms had filibustered the bill and denounced Dr. King on the floor of the Senate as someone who advocated “action-oriented Marxism” and other “radical political” views.

Where Does the Holiday Stand Today?

Although Martin Luther King Jr. Day is commemorated by the federal government and, in some form, by all 50 states, some, like Arizona and Idaho, combine commemorations of Dr. King’s birthday with a holiday to honor civil rights.

Biloxi, Miss., drew backlash on Twitter last week after the city’s official Twitter account posted an alert to residents about closings on “Great Americans Day.” The tweet was later deleted.

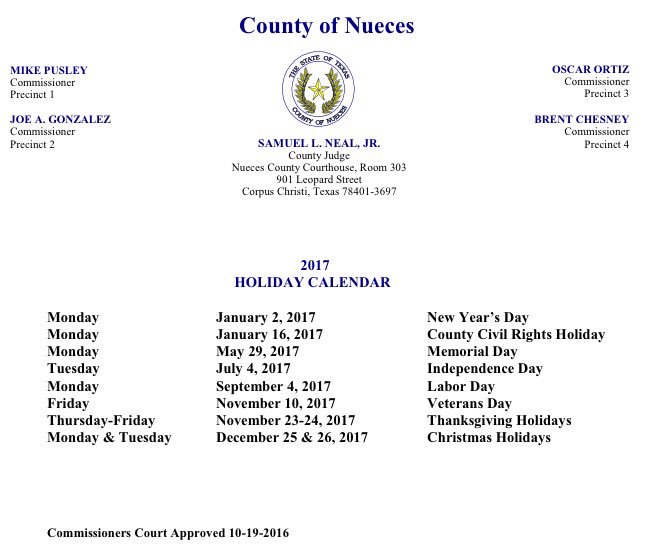

A release by Nueces County, Tex., referred to the day as a “County Civil Rights Holiday.”

And then there are a few states in the Deep South — Arkansas, Alabama and Mississippi — that combine celebrations of the civil rights icon and a Confederate general: Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert E. Lee Day. Lexington, Va., even uses it to honor Lee and another Confederate general, Stonewall Jackson.

Critics have decried those arrangements as an unholy merger that commemorate both freedom and slavery — a combination that is nonsensical at best and inflammatory at worst.

Arkansas lawmakers have tried in recent years to separate the two holidays, but the measures have been opposed from constituents who call the effort an affront to Southern heritage or by lawmakers who say they have better things to do.

“We’re looking for a solution to a problem we don’t have,” Josh Miller, a Republican state representative in Arkansas, told The Associated Press. “I haven’t noticed any humongous Robert E. Lee parades that are taking place in conjunction with Martin Luther King Day.”

P.C: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/16/us/martin-luther-king-jr-the-confederacy.html?_r=0

Post a Comment